It’s so much fun to birdwatch at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s a way to look at familiar pieces of art in a new way, to find a focus when walking through imposing galleries with walls and walls of art screaming for attention. Now that the Met Museum has reopened after being closed for way too long because of COVID-19, I have been looking forward to returning to bird again. When I visited the Making the Met 1870-2020 exhibition on September 10, I was able to find quite a few delightful birds in the Met’s illuminating showcase of its history. The exhibition is definitely worth a visit, and finding the birds really helped me see all the art.

This stele was in the first room of the exhibition, and it was so touching how the young girl was speaking to her doves.

Marble grave stele of a little girl, ca. 450–440 B.C. Greek

Most of the art featured here appear in the order seen while walking through the exhibition, although there are exceptions. And I did throw in two ringers at the end from the Chinese galleries, since I did a brief walk through at the end of my Met visit. And by the way: the Met’s Web site now has a Birding at the Met icon on its The Met Collection page!

Above: Eagle Relief, 10th–13th century. Toltec. This stone panel depicts an eagle biting into a cactus fruit, symbolizing the sun devouring a human heart.

Right: Raven rattle, 19th century, Native American (Tsimshian). Raven rattles, used to channel a shaman's spirit guide, are held oriented with the bird's beak pointing down when used in dance. They were used in healing ceremonies.

Although the Courbet and Manet paintings are in different exhibition rooms, I show them here because the Manet painting is thought by some scholars to be a rejoinder to Courbet’s work.

Edouard Manet, Young Lady in 1866, 1866. French. According to some scholars, the parrot-confidant represents the sense of hearing.

Gustave Courbet. Woman With a Parrot, 1866. French. When this painting was shown in the Salon of 1866, critics censured Courbet's "lack of taste," as well as his model's "ungainly" pose and "disheveled hair." But the painting was admired by younger artists who wanted to reject academic standards.

Detail, Gustave Courbet, Woman With a Parrot.

While the Rembrandt in the Making the Met exhibition is notable as one of the paintings that helped strengthen the Met’s reputation as a world-class museum, I include it here because of the peacock in the lower-right corner, almost too dark now to see. (I will note here that there are some fantastic works of art in this exhibition, including paintings by Anthony van Dyck, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt, El Greco, Pablo Picasso, Vasily Kandinsky, Romare Bearden, Edgar Degas, and other luminaries, but they didn’t include birds, so I don’t include them here. But I did look for birds in those paintings, and thus looked at them in a new way. And I recommend an amazing work I have never seen before, “Street Story Quilt,” by Faith Ringgold. I looked for birds, but found history and humanity.)

Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn). The Toilet of Bathsheba, 1643. Dutch

Detail: Rembrandt, The Toilet of Bathsheba

The Met has such a wide variety of art objects, including textiles. These birds were roosting in cotton and silk threads.

Merton Abbey Tapestry Works. Strawberry Thief, design registered 1883, printed 1917–23. Medium: cotton. British

Detail: Strawberry Thief

Panel with grotesques, from a set of bed hangings, ca. 1550–60. Medium: Silk, wool, silver and silver-gilt thread. Related to the prints of Cornelis Floris II. Netherlandish

Above and below: Details, Panel with grotesques

Left: Caleb Gardner. Easy Chair, 1758. New England (New Port). Eighteenth-century easy chairs—heavily padded, with thick down-filled cushions—were often reserved for the elderly or the infirm. The front is covered with Irish stitch needlework and the back with a needlework landscape scene. Below: Detail, Caleb Gardner Easy Chair

Left: Vase With Immortals Offering the Peaches of Longevity. Medium: Porcelain, overglaze enamels. China. A peacock-like phoenix has landed near a group of men and their attendants burning incense.

Above: Detail, Vase With Immortals Offering the Peaches of Longevity

Striding Thoth, 332–30 B.C. Ptolemaic Period. Thoth is the god of writing, accounting and all things intellectual. He can be portrayed as an ibis, a baboon, or a human body with an ibis head.

Bowl With a Figure and Birds. 10th century. Purchased at Nishapur, Iran; acquired through partage, 1938. Earthenware; polychrome decoration under transparent glaze (buff ware)

Dagobert Peche. Bird-shaped box, 1920. Austrian. This box in the shape of a fantastical bird is an example of the work produced by the Wiener Werkstätte.

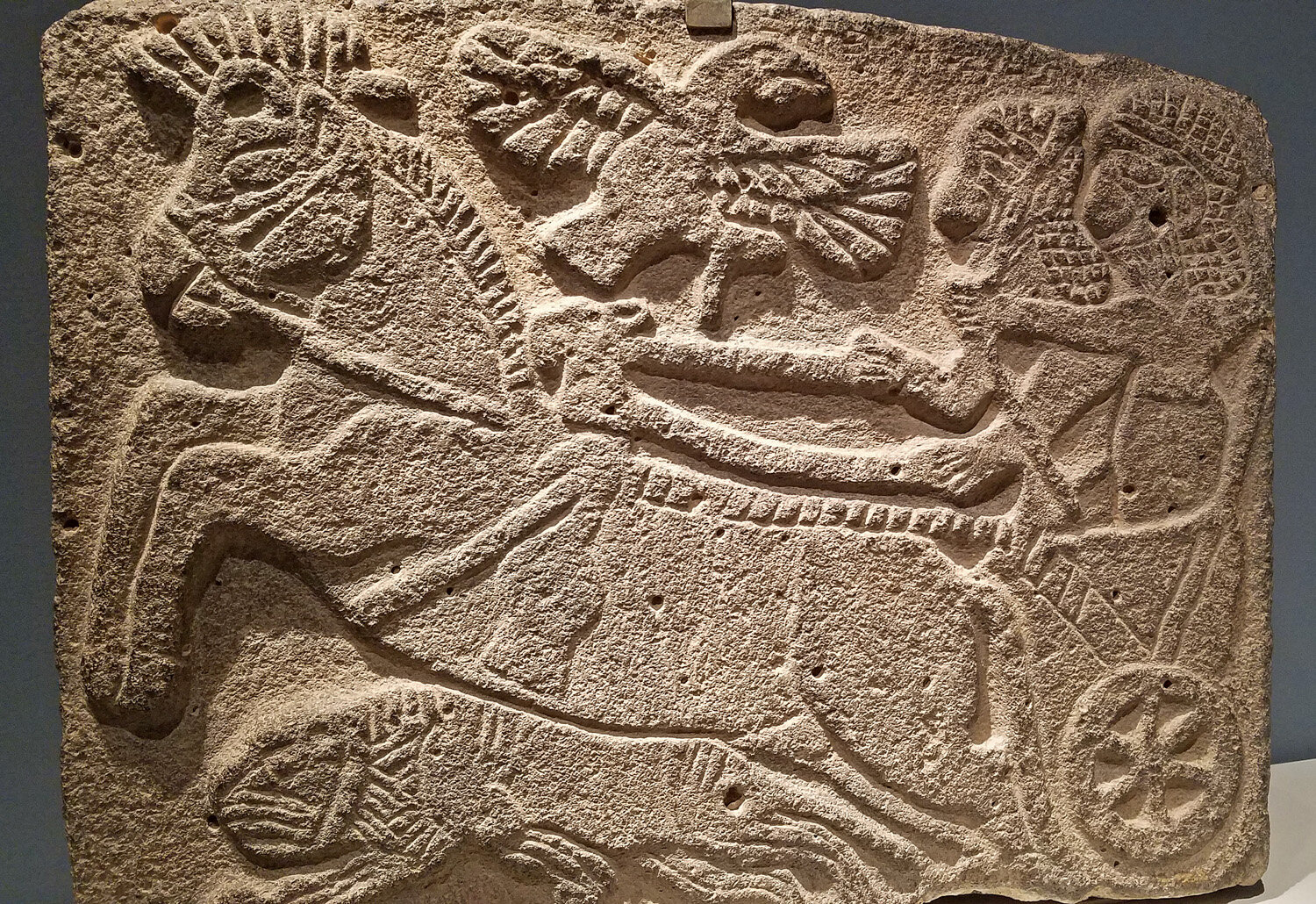

Orthostat relief: lion-hunt scene, ca. 10th−9th century B.C. Hittite. Stone slabs carved in low relief had traditionally decorated the walls of the Neo-Hittite palaces and temples.

When I first visited the Met Museum in the 1970s, I loved the Greek collection. As part of my theater history class, we were advised to visit the statues and pottery to get a feel for how the Greeks viewed art, religion and theater. The amphora below, depicting Athena, was one piece I remember, although at that time I didn’t concentrate on the roosters on both sides of her.

Left: Attributed to the Euphiletos Painter. Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora, ca. 530 B.C. On the other side of the amphora is a footrace. Above: Details of the roosters on both sides of Athena.

Sometimes I walk by works on paper without really seeing them, and I have found looking for birds (or other animals) to be a way to concentrate my attention so that I can appreciate what I am seeing.

Balachand. “Jahangir and his Father, Akbar,” Folio from the Shah Jahan Album, verso: ca. 1630; recto: ca.1540–50. The artist visualizes Emperor Jahangir raising his hands in a supplication for his father, Akbar, who is holding a falcon.

Left and above: Details, Balachand, “Jahangir and his Father, Akbar”

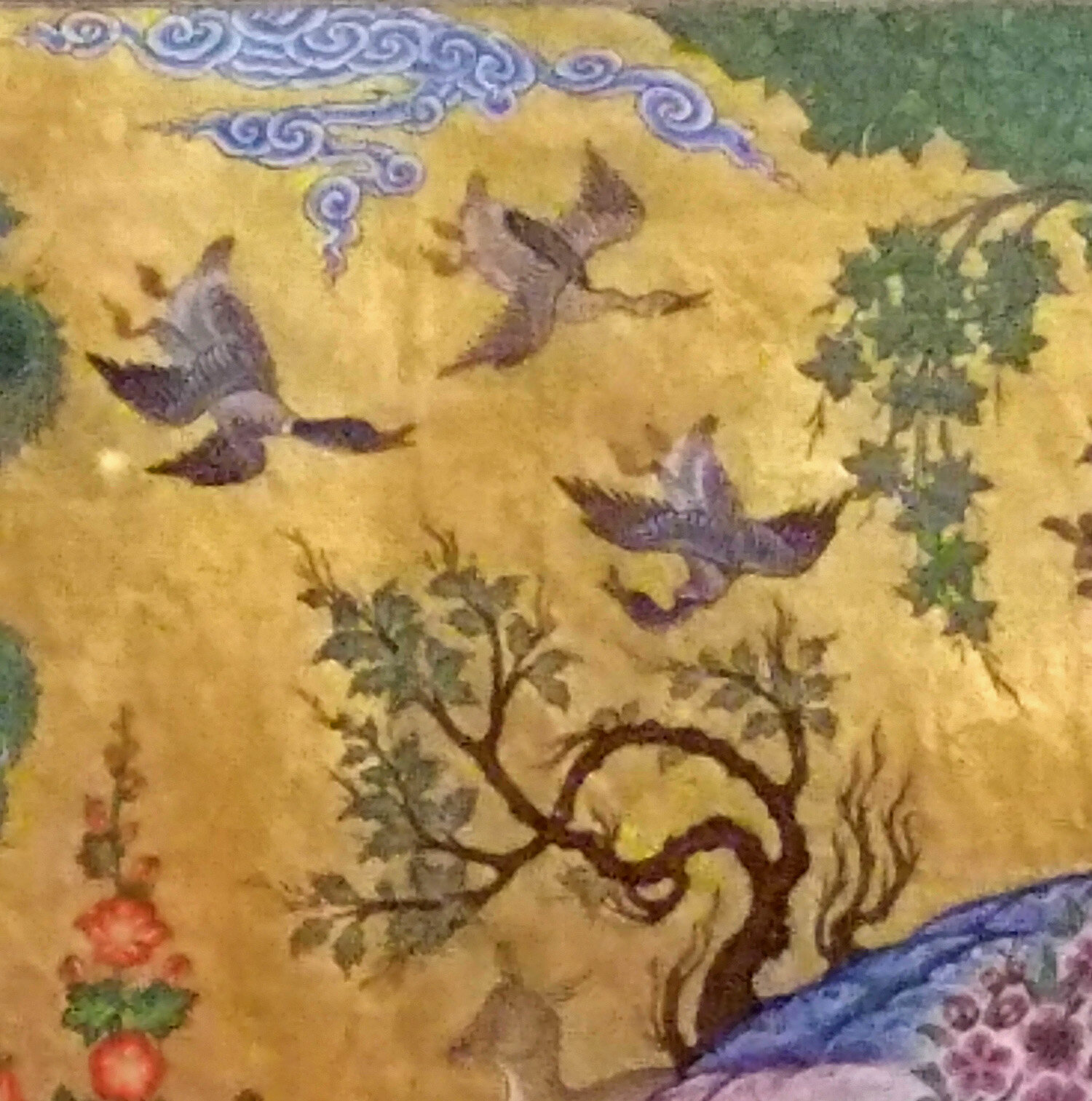

Attributed to Basavana. “Assad Ibn Kariba Launches a Night Attack on the Camp of Malik Iraj.” Folio from a Hamzanama (The Adventures of Hamza), ca. 1564–69. The Hamzanama relates the story of Hamza, an uncle of the prophet Mohammad. In this scene, Assad ibn Kariba, a supporter of Hamza shown dressed in an orange jama, takes an army of unbelievers by surprise in a night attack.

Detail, showing herons in the tree, “Assad Ibn Kariba Launches a Night Attack on the Camp of Malik Iraj”

Abu'l Qasim Firdausi. "Kai Khusrau Rides Bihzad for the First Time," Folio 212r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmaspca. 1525–30. Giv and Kai Khusrau need to find Bihzad, Siyavush's mount, who has been allowed to run wild in the mountains since his master's death.

Detail, “Kai Khusrau Rides Bihzad for the First Time”

Water dropper in the shape of a crane, 18th century. China. A crane holding a branch of peaches symbolizes longevity.

After viewing the Making the Met exhibition, I wandered through some other galleries, which I thought were a bit too crowded to appreciate safely. I found fewer people in the China galleries—and more birds, including some Mandarin ducks (Woody’s cousins in Genus Aix) and some gorgeous hawks.

Left: Lü Ji. Mandarin Ducks and Cotton Rose Hibiscus, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), late 15th century. Chinese. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk. Lü Ji, a professional painter from Zhejiang Province, worked in the Southern Song (1127–1279) ink-wash style, which had remained popular in that region through the intervening centuries. The pair of ducks connote a happy marriage.

Details, Lü Ji, Mandarin Ducks and Cotton Rose Hibiscus

Left: Lin Liang. Two Hawks in a Thicket, mid-15th century. Chinese. One of the leading court painters of bird-and-flower scenes, the Cantonese artist specialized in bold, expressive, monochrome depictions of birds in the wild.

Below: Detail, Lin Liang, Two Hawks in a Thicket. To paint the tail of the bird on the right, the artist left an area of unpainted silk around the quickly applied dark ink of the feathers so that they contrast with the background.

Most photographs in this blog entry were taken with my cellphone, but some public-domain photographs from the Met Museum’s Web site are also included. The captions and descriptions are adapted from information on the Met’s Web site, as well as the descriptive cards next to the art in the exhibition.

A note about visiting this exhibition. The Metropolitan Museum of Art now requires timed admissions to enter the museum, and you must wear a mask. I visited on September 10, and was able to get a time for the second hour of admission at 1 p.m. The Making the Met galleries were not that crowded for the first hour I was there, but by 3 p.m. the museum was almost as crowded in some galleries as before the pandemic. I visited some less crowded galleries, but then left the museum rather than risk exposure from being close to so many people in an indoor environment.

Your Chronicler last birded the Met in November 2019, resulting in a Birding the Met Museum blog entry. This Web site concentrates on bird photography and videos, but occasionally other artists get to appear here to show off more feathers.,